Like all things 2020, Cleveland VOTES’ National Voter Registration began with the blissfully ignorant best laid plans of an organization who thought the year would be“normal.”

Founded in 2014 as a nonpartisan, democracy-builder in the city’s metro area, Cleveland VOTES was riding high on past voter registration success in pre-COVID 2020.

Founded in 2014 as a nonpartisan, democracy-builder in the city’s metro area, Cleveland VOTES was riding high on past voter registration success in pre-COVID 2020.

“We had been planning for 2020 since 2018,” said Jennifer Lumpkin, Civic Engagement Strategy Manager for Cleveland VOTES, noting a $325,000 grant from the Gund Foundation they’d received to help seed the get-out-the-vote efforts implemented in the midterm.

With equity in civic engagement existing as the organization’s bedrock principle, Cleveland VOTES previously identified a combination of digital redlining of online voter registration tools and lack of transportation as the two biggest barriers to GOTV in the city’s underserved communities.

As a remedy, the group was on track to rapidly expand upon a 2019 Ride to the Polls initiative, which would now provide more targeted support to disabled populations.

And then March happened.

“Right at the beginning of March, I was making calls out to all of our volunteers for the ‘Ride to the Polls’ program,” Lumpkin wistfully recalled. “In the throes of a literal pandemic.”

Tasked with going back to the drawing board in the middle of the “new normal” that was the Spring wave of the pandemic, Cleveland Votes looked to its 54-member team of partners (brought together the strongest mobilizers)and carved out a new roadmap for voter registration in the time of the ‘rona.

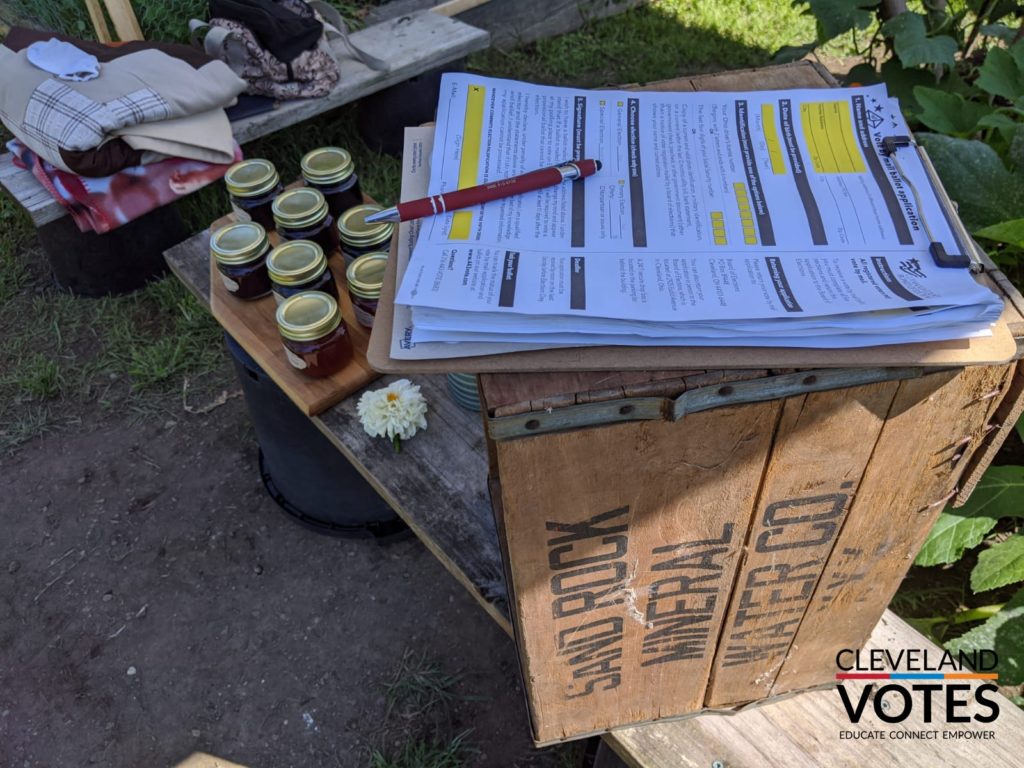

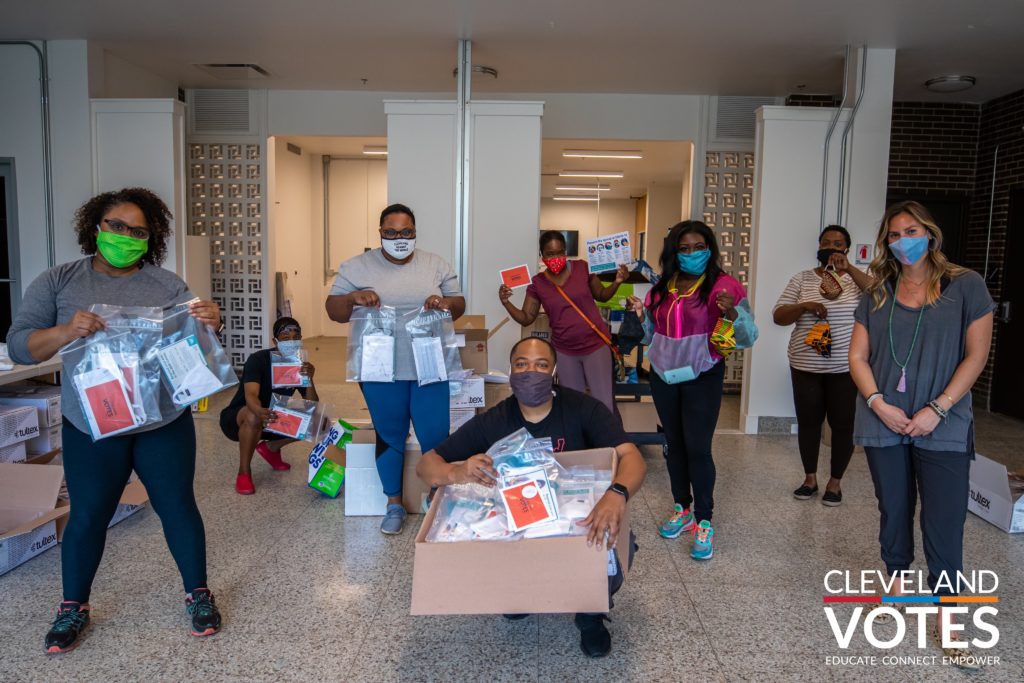

Ironically, one solution to ensure their community was #VoteReady, arrived in tandem with the very real and new health crisis: a shortage of masks that left Cuyahoga County one of Ohio’s hardest hit areas. In an effort to kill two birds with one stone, Cleveland Votes developed the “Masks for Community Voter Drive-Through” that would serve a threefold-purpose as a mask giveaway and a distribution hub for voter registration information and vote by mail applications.

The format could easily be replicated by Cleveland VOTES partners, Lumpkin said, with the organization’s previous “Ride to the Polls” hotline being revamped to updates on where the mask drive throughs could be found.

“It was an opportunity for our grantees and partners to say ‘we need 500 kits to distribute at our church on Sunday. Can you deliver those so we can essentially do a voter registration drive-through?’” Lumpkin said. “They were one-stop shops where you would be able to receive [voting] information, get a free mask, get a free breakfast, and receive your vote by mail application.”

“It was an opportunity for our grantees and partners to say ‘we need 500 kits to distribute at our church on Sunday. Can you deliver those so we can essentially do a voter registration drive-through?’” Lumpkin said. “They were one-stop shops where you would be able to receive [voting] information, get a free mask, get a free breakfast, and receive your vote by mail application.”

All in all, the network of Cleveland VOTES partners distributed over 70,000 mask kits, a task that Lumpkin said was only possible because of all the organization’s pre-2020 work to “provide multiple modes of communication and ways for folks to access us.”

When National Voter Registration Day itself rolled around that Fall, Cleveland VOTES was determined to outdo their voter registration success in 2018, when the organization was among the top ten voter registration efforts in the country.

Typically, organizations set up shop at libraries, homeless shelters, food banks and other community touchpoints where volunteers would register voters, hand out snacks, take pictures, and revel in the pre-pandemic democratic joy.

However, in 2020, they found themselves in a new location: camped out on the court of the same Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse where the Cleveland Cavaliers played.

“That’s where we were,” Lumpkin said through a laugh. “We were kind of stressed between the additional pre-planning and communicating with folks ahead of time that was needed and the visits from people like Secretary of State [Frank LaRose.]”

It was a memorable day to be sure, but Lumpkin says the moment that sticks with her most was an interaction with a young female artist with a newborn baby who was uncertain as to whether or not she planned to vote in 2020.

“I could have said ‘OK, fine. Don’t do it. Whatever,’” Lumpkin said. “But having the empathy and the ability to relate and say instead that ‘I’m not telling you that you have to do anything, but if you want to have options later you need to register and if you want to do it safely, you need to apply for this vote by mail application and you need to apply for it now.’ You can’t really explain it, you just have to feel it and understand. It’s the kind of communication I’m not sure that woman would have heard if it wasn’t me having that conversation with her. We were very close in age and I felt like I could relate to her.”

The ability to relate went much deeper than age, according to Lumpkin, who noted that she hadn’t always been the vocal advocate for getting out the vote that she is today.

“I did not believe in voting or registering to vote prior to working in this space; I believed in building democracy in other ways,” said Lumpkin, who also serves as a Black Lives Matter organizer in the Cleveland area.

“But now, I truly think that what keeps me coming back is that a part of me understands why people are frustrated or lack confidence. I can relate to folks in a way that’s largely missing from so many outreach efforts. I do it because I feel necessary, I feel needed, and I know that there are people who came before me who were oppressed and just didn’t have the choice.”